UN boss António Guterres has a long habit of cuddling with dictators.

Ukrainians were furious when they saw the United Nations secretary-general bow to Vladimir Putin. Yet the Portuguese diplomat has a habit of coddling dictators. And it's killing the UN.

BY MICHAEL ANDERSEN

This photo made Ukrainians all over the world furious. It shows United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres bowing to Russian dictator Vladimir Putin at the BRICS summit meeting in Kazan from Oct. 22-24. Ukrainians all over the world posted their disgust and anger with the UN boss. Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky called off a meeting with Guterres planned for the day after the BRICS summit.

At first, the angry outbursts were mainly focused on the moral bankruptcy of the head of the UN smiling and bowing to Putin, whose decision to invade Ukraine in February 2022 has resulted in the death of hundreds of thousands and forced 7 million Ukrainian to flee their country, many thousands have been tortured and raped.

To be fair to Guterres, he has on several occasions condemned the Russian invasion of Ukraine. But many Ukrainians are deeply upset by the photos of him cozying up to a dictator destroying their nation.

Many also focused on the fact that, in 2023, the International Criminal Court (ICC) issued an arrest warrant for the Russian leader for the illegal deportation of thousands of Ukrainian children to Russia. This should have prevented Guterres from meeting him. The UN guidelines are clear: “As a general rule, there should be no meetings between United Nations officials and persons who are the subject of warrants of arrest issued by the International Criminal Court.” Therefore, Guterres seems to have broken the UN guidelines, and a coalition of Ukrainian nongovernmental organizations is asking the UN General Assembly to take action against the secretary-general.

Guterres also hugged the Belarusian dictator Aleksandr Lukashenko.

At the time of writing, it is still uncertain whether this will have consequences for Guterres’ tenure. But what is certain is that this is not the first time that Guterres, in his role as UN boss, angered people by being soft on post-Soviet dictators. It’s a pattern for Guterres.

2017 - Guterres goes to Central Asia

In my previous life, I worked and lived in Central Asia for many years. This stunningly beautiful part of the world has forever, it seems, been beset by murderous, corrupt rulers. In fact, of the five “stans,” only in Kyrgyzstan do the rulers even pretend to care about democracy.

Over the last decade, even Kyrgyzstan – for a short while about 20 years ago dubbed “the Island of Democracy in a sea of dictatorships: – has been sinking back into the ugly quagmire of the rest of the region – the hardline dictatorships of Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, and Turkmenistan. The West is nowhere to be seen out here. We lost interest when Afghanistan fell, if not before.

To this God-forsaken region - democratically speaking - Guterres arrived in June 2017, only six months into his post. At that point, Kyrgyzstan was the only country in the region considered “partly free: by Freedom House in their respected annual Freedom Index. The other four “stans” were, as they have always been, marked “not free.”

This demonstrable lack of democracy, however, did not in the slightest make the new UN boss hesitate to praise the local regimes. Guterres started in Kazakhstan. He had even timed his visit to coincide with the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation summit (SCO) – an organization controlled by China and Russia, mainly to keep the former Soviet republics under control. It is often referred to as an anti-Western dictator club. (More recently, Belarus, Iran, and India joined, hardly improving the SCO’s democratic credentials).

This was the first time that a UN secretary-general had ever participated in an SCO summit. Kazakhstan’s dictator, Nursultan Nazarbayev, who had been in power for a mere 26 years, praised Guterres and called his participation “historic.” Guterres congratulated Nazarbayev on a successful SCO summit: “The SCO is gradually becoming the center of gravity all over the world. This organization, in my opinion, is an important foundation of today’s world order.”

Kazakhstan was in the middle of yet another crackdown on independent media and free expression, but Guterres did not even meet with civil society representatives.

The next stop was Uzbekistan, where Guterres met with Uzbek President Shavkat Mirziyoyev, who only eight months earlier had taken over from the long-term dictator Islam Karimov, who died of a heart attack sitting on his toilet made of gold. When he died, Karimov was in power for 25 years.

Karimov was known as the “Butcher of Andijan” after his army in 2005 had massacred more than 1,000 mainly peaceful demonstrators in the city of Andijan. His regime was one of the harshest in the world, with an estimated 12,000 political and religious prisoners. I have interviewed hundreds of victims about the most brutal torture you can imagine, including a family whose father had been boiled to death.

Against that background, it was strange that Guterres’ first business point in Uzbekistan was to pay homage and lay flowers at Karimov’s mausoleum in Samarkand.

Understandably, my human rights defender friends in Uzbekistan were appalled. But having spent years in prison, often under torture, they were also clever enough to keep quiet. As you can see, I had trouble containing my anger.

The new president, Mirziyoyev, pretended to want to reform, of course, but seeing as he had been Karimov’s prime minister for 13 years, only fools believed him. Obligingly, Guterres noted that the reforms being carried out in Uzbekistan were “of great importance to improving the well-being of the people and prosperity of the country.”

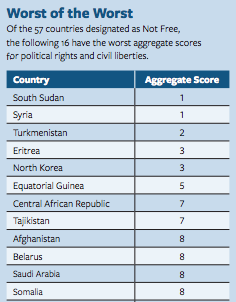

Freedom House was not quite as impressed as Guterres. In its analysis of political freedom and rights in Uzbekistan in 2017, the Freedom House gave the regime a 0. Literally 0 political rights. Turkmenistan scored 0 on political rights, and Tajikistan scored 1. In Tajikistan, which Guterres visited amid the heaviest crackdown on the minute political opposition for 20 years, there is no sign of Guterres mentioning political freedoms and democracy. Instead, he praised the Tajik regime and the country’s president (in power for 23 years) for “having made remarkable progress” in fighting poverty. Most focus on the fact that the country is among the most corrupt in the world, which rarely bodes well for fighting inequality.

Then Guterres continued to Kyrgyzstan, praising “a regime based on the rule of law, the protection of human rights, with a vibrant civil society, making Kyrgyzstan the pioneer of democracy in Central Asia.”

Several human rights organizations publicly disagreed with the secretary-general, protesting explicitly against Guterres and his (at best) naïve praise of the government. “We don’t trust the UN Office,” some said. At the same time, the country’s leading human rights activist, Aziza Abdrasulova, explained that the UN closely works with Kyrgyzstan’s government and thus “became as if it’s one of the [government] departments, working with the instructions coming from Kyrgyz government.” She said, “The UN should address human rights issues, but it keeps ignoring them.”

As I said, I worked for many years in the region as a teacher and journalist. Few Central Asians had any faith in the UN. When I lived in Tashkent, local NGOs established a ranking system for which UN organizations were the most corrupt and, thus, made it easy to siphon money off. Anecdotes about lovers, fathers, mothers, brothers, sisters, and cousins being hired were ad libitum.

(from The Times of Central Asia)

2024: ‘Nobody really gives sh.. about the UN boss any longer’

Seven years later, in July this year, Guterres visited Central Asia again. This time, he kept his visit to opening new UN buildings and praising local culture and produce, not a word about politics from the UN boss. This was probably a wise choice, seeing as none of the praise he had delivered to the regimes back in 2017 had come to fruition; quite the contrary, it had made him look decidedly foolish. By now, Freedom House was labeling all the countries in the region as “not free.”

Human Rights Watch listed a whole litany of very serious transgressions in all five countries of the region during 2023: Massacres of 225 protesters (Kazakhstan), repressive laws and bogus court cases, cracking down on free media and civil society (all), torture in detention and prisons (all), lack of free courts (all), lack of political reform (all), extreme corruption (all), zero or limited political freedom (all).

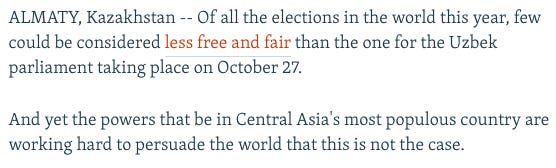

The watchdog Reporters Without Borders uses a 100-point scale for media freedom. On that, Uzbekistan has fallen to 37.27 from 46.48 since 2019, as several of the bloggers that emerged during the ‘thaw’ – the one that Guterres was so happily touting in 2017 – later found themselves on the end of harsh prison sentences. This past weekend, Oct. 27, Uzbekistan held “elections” for its ‘parliament’ - no independent candidates were permitted to run, and no new political parties were allowed to register. There is no prize for guessing the result.

One observer described the seance thus:

By now, Tajikistan’s ruler Emomali Rakhmon has been in power for 30 years (although there are constant rumors that he soon may hand over the country to his son), and Tajikistan, Turkmenistan and Belarus were competing with South Sudan, Syria, and North Korea to be the, in the words of Freedom House, “the worst of the worst.”

Like in 2017 and 2024, Guterres timed his visit so he could participate in the summit of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO), which is celebrating Belarus as its latest member. The SCO has not criticized the Russian invasion of Ukraine so far. In fact, Vladimir Putin is now clearly trying to turn the SCO into an instrument he can use to circumvent Western sanctions. And it is, to a large extent, working.

In 2024, in contrast to his visit seven years earlier, Guterres’ visit got almost zero attention - not from human rights activists, not from the tiny pockets of independent internet media. When I asked them why they no longer engaged, their answers were striking: “Why should we?” a long-term acquaintance of mine responded, “the UN in Central Asia is corrupted through and through, and Guterres is the perfect illustration of this, he flies in, shakes hand with the über crooks, a few photo ops with local kids have been pre-arranged, and he flies out again. Tick.”

An analyst from an international organization told me that “there is a feeling that all is lost, and ‘nobody really gives sh…about the UN or its boss any longer”

International media also ignored the visit. Interest has dwindled after the U.S. exit from Afghanistan in 2020-21. “The rulers here just go about their business. Even they find the UN capo irrelevant—apart from him shaking their hand and smiling on TV, and then goodbye,” says a local opposition politician. For years, he himself has been in and out of police detention, with several criminal cases hanging over him and his family.

For obvious reasons, these people all want to stay anonymous. And that is probably as good a yardstick as any for measuring how democracy and freedom are faring in Central Asia. Guterres met all of the Central Asian leaders again a few months later at the BRICS summit in Kazan, Russia.

So, there you have it: The UN secretary-general’s respectful scraping in front of the war crimes indicted Russian dictator in Kazan last week was not an exception but more a rule. It made many Ukrainians furious - in many other countries of the former Soviet Union, local human rights defenders and journalists don’t even have the option of protesting.

The result is the same: Antonio Guterres is losing the United Nations its final drops of respect.

The UN was neutered a long time ago as the dictators from China and Russia used their sway in the Council to derail meaningful action. Many of the UN’s agencies have fallen into the same trap. It is long overdue that the UN receive an overhaul and the corruption within be rooted out and the offending states suspended for a period of time to consider their abuse of privilege. Ukraine should not expect any favours from the UN. Their best option is to continue on their path to NATO and the EU.

Wasn’t just Ukrainians who were furious…