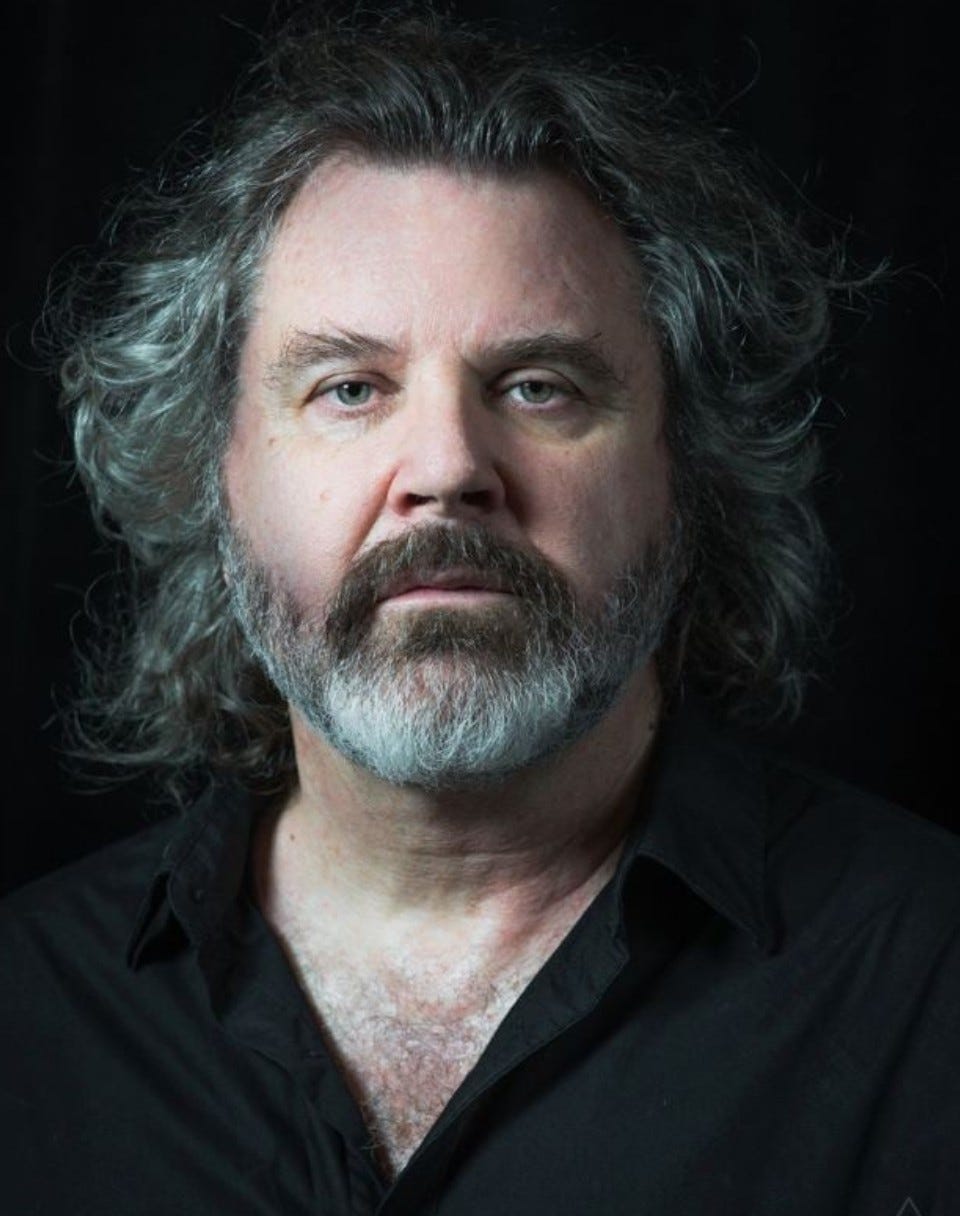

BLITZ INTERVIEW: John Freedman fights for Ukraine with theater, literature and films

After decades in Russia, he and his wife, the actress Oksana Mysina, had to leave after she spoke out against Putin's war on Ukraine. "The resilience of Ukrainians is amazing," the American says.

(photo by Lyubov Orlova)

Where are you from? And where are you now? What work are you doing now?

I'm originally from the town of Apple Valley, California. It's been a joy all my life to say I was born and grew up in the desert (the Mojave). It gets great reactions from people who imagine nothing but swirling sands and sun-burnt animal carcasses. Of course, it's not quite that, but there were lots of cacti, lizards, and Joshua trees. I have spent significant time in different cities in the U.S. and decades in Moscow. I currently live on the Greek island of Crete. I essentially continue the work I have done for most of my adult life – writing and translating. Four years after relocating to Greece, I had the great fortune of making one of my most important (virtual) acquaintances – Nina Kamberos, the founder of Laertes Press in the US. In the last year and a half I have produced four books for Laertes as editor/translator, and we have that many again in preparation for the near future. After years of working with numerous publishers that couldn't have cared less about me or my work, I have found a writer's heaven in Nina and Laertes.

It needs to be said that my wife, Oksana Mysina, and I were finally compelled to leave Russia in 2018. We married in Moscow in 1989 and had remained there ever since. Oksana was a leading actor in film and theater, and I was the theater critic for The Moscow Times, as well as a freelancer for several Western publications and author and/or compiler of several books. We were aware of deep-state eyes upon us at all times – they remained in the shadows when they wanted, but also made themselves perfectly visible when they wanted to. When Oksana began speaking out against the war in Ukraine in 2014, it had immediate repercussions on her career. Her film work dried up almost immediately, and her work in theater was marginalized. So, that's a substantial story between “residence in Moscow” and “residence in Greece.”

(Oksana Mysina with awards for her film “Escape” in Santa Monica 2023)

Oksana has reinvented herself as an experimental filmmaker in Greece, which has pulled me into new territories. I am now a producer, cinematographer, cameraman, and jack-of-all-trades in Oksana's and my little Free Flight Films studio. We have completed nine films (shorts and feature-length) that have done very well on the festival circuit. We have at least four more in the works—I forget the exact number. Oksana is a prolific workhorse. I run along behind her, trying to keep up.

What is your 'connection' to Ukraine? How has the war changed your life, changed you personally?

I hesitate to call it a connection. That seems too clinical and too superficial for what the reality is. Since the early days of Russia's full-scale invasion, Ukraine and dozens of Ukrainian playwrights have become my life's and life work's focus, my extended family, and my moral support in times of madness. Aside from that, Oksana was born in Ukraine in the Donbas region. Even after her parents took the family to Moscow in the late 1960s, she would return for the proverbial summer vacations with her grandparents. She still has relatives there, some of whom she convinced to evacuate to Greece in the early days of the hot war. They are still here with us in safety, for which we are all very grateful. Oksana made a beautiful short film, “Escape,” about their hurried exit from Ukraine as the war began. Within days of the war’s start, I began cobbling together relationships with various Ukrainian writers, old friends, and new. Two years earlier, during the failed revolution in Minsk, Belarus, I had done something similar with the Belarusian playwright and filmmaker Andrei Kureichik – an international program promoting Andrei's powerful plays about the revolution. We called the project the Insulted. Belarus Worldwide Readings Project after his first play, Insulted. Belarus. So when Putin maniacally declared that there is no such thing as Ukrainian culture, Ukrainian language, or even a Ukrainian homeland – and followed that up by sending death and destruction to his neighboring country – I applied my experience to create the Worldwide Ukrainian Play Readings (WUPR), a sizeable play-reading program giving voice to my Ukrainian colleagues. I began by reaching out to my long-time friend, the playwright Maksym Kurochkin, who was then creating a new Kyiv venue called the Theater of Playwrights along with 19 of his colleagues. Through the Theater of Playwrights, I began receiving dozens of texts, sometimes written days before, in which these and other writers were recording the day-to-day and occasionally minute-to-minute trials of experiencing war blowing up in their faces. At last count, WUPR had helped organize some 670 readings, performances, films, videos, conferences, translation workshops, etc., in 31 countries. Twenty of these texts went into a book I edited for Laertes Press: “A Dictionary of Emotions in a Time of War: 20 Short Works by Ukrainian Playwrights.” I am pleased to say that in its list of the 50 best books of 2023, The Telegraph listed our book at number 21. Just recently, we received a Bronze IPPY in the Current Events (Social Issues/Humanitarian) category of the prestigious IPPY (Independent Publisher Book) awards.

(Poster for Worldwide Ukrainian Play Readings)

A detour is required here: My second language is Russian. I have a limited, passive knowledge of a few other languages, including Polish and Slovak, but I have never worked professionally with any language besides Russian. I received half a dozen or more new Ukrainian-language texts a day (in March/April 2022), which needed to be translated quickly and distributed. And so I enlisted the aid of Nataliia Bratus, Oksana's cousin from Ukraine, who had just arrived in our little Greek idyll. We began working on translating the texts together. We made a very good team, and we're still working together two years later. My reading command of Ukrainian had improved significantly at that time, but I would never have attempted to take on a Ukrainian translation without Nataliia beside me. You don't break up good teams. I see us as the Glimmer Twins or Lennon-and-McCartney of Ukrainian drama translation.

It should be clear that the war has changed my life utterly. After over 40 years as a scholar, researcher, and translator of Russian themes, I am completely committed to Ukraine and Ukrainian drama and theater, continuing with some of my efforts in Belarusian drama.

The war has also changed me personally in every way possible. The stress of watching closely what is happening is debilitating. The one thing that has saved Oksana and me from going mad over these two-plus years is that we are making useful contributions that enable Ukraine and Ukrainians to stand their ground. Of course, our impact is minuscule when measured against the hell that Ukrainians go through every day. But we are committed to doing what we can. We put our heads down and work, hoping against hope that sooner rather than later, we will lift our heads in a legitimate, not apocalyptic, post-war scenario.

What has surprised you most about Ukrainians these past couple of years? Good or bad? Tell us one thing you don’t think people abroad know about Ukraine – but they really should?

Indeed, Ukrainian resilience is the greatest discovery I have made during this period. The tough, tensile, but utterly unbreakable Ukrainian character. That, and their almost unshakable belief that justice, good, and right must and will prevail. It is something that we Americans have come close to losing, what with the post-truth, post-honesty, post-dignity era that has come to reign in the United States. Meanwhile, we watch the extreme right (go ahead, call them fascists or neo-fascists) continuing to surge here and there in Europe and elsewhere. It is so unfashionable to believe in democracy and justice as the Ukrainians do! I don't know if enough people are out there to appreciate the lesson, but, to my mind, Ukraine is giving the world a lesson in grace and nobility.

I recently published an interview with the Kharkiv playwright Dmytro Ternoviy. He told in great detail what it is like to live and work in a city under siege. But even he was astonished by the response to a public call to raise money to buy vehicles for local soldiers: “Kharkiv channels announced an urgent collection to purchase three relatively inexpensive vehicles for the front,” he said. “Cars are expendable commodities in war; they usually last just a few trips. So this channel announced that it needed to collect 600,000 hryvnia (about $15,000). Then, they closed the call for donations six minutes later because the entire amount had been collected. I never cease to be amazed.”

All of the writers I work with — and not only they — donate large sums of their meager earnings to the war effort for equipment, cars, medical supplies, clothing... It is a national effort that virtually every Ukrainian takes for granted – that whatever extra they may have should be donated to the general good. Early in the war, collaborating with my great, late colleague Philip Arnoult and his Center for International Theater Development, we arranged for some 30 significant grants to writers of the Theater of Playwrights. Later, I learned that virtually every writer who received a grant had turned over a substantial percentage of their money to the war effort.

I'll repeat it: There is something incredibly “old-fashioned” in this! By that, I mean something that I remember being a part of my life 50 or 60 years ago (I am now 70), which is now largely lost. Think about it: Can you imagine an American politician following President John F. Kennedy's lead and hoping to inspire and attract voters by saying something like: “Ask not what your country can do for you – ask what you can do for your country”? That is precisely the golden rule that virtually all Ukrainians live by today.

(John Freedman speaking at an Open Russia event in London)

What are your plans?

My life is essentially on hold until the war against Ukraine is stopped. Every breathing moment that Oksana and I pass in a day is colored by, influenced by, and determined by the war. We are “fighting” it as best we can in the ways available to us. I will continue to promote the opportunity for Ukrainian writers to use their art in the battle against oblivion. Oksana and I will continue to make films that speak out against the war in some way. We both see ourselves as living incarnations of Edvard Munch's painting, “The Scream.” We will continue to shout until we discover a better, more successful way of supporting people and influencing public opinion.

How do you see the war ending and Ukraine returning to a normal life?

I have no crystal ball. In my time, I have made a few ill-advised attempts at “predicting” the future – more specifically, the demise of Vladimir Putin – and I have always been miserably wrong. Ukraine, and those of us who support it, are in the fight of our lives. Putin is a hardened criminal, a sociopath. He is not a politician; he is not the leader of a nation. He is a criminal who has turned Russia into his personal criminal fiefdom. His desire to reanimate the Soviet Union and expand it is doomed historically. But how much death and devastation can he wreak before that deranged ambition collapses?

Until he and, more importantly, those supporting him are removed from the political equation, we will be walking on a razor's edge. And, as long as danger continues to emanate from the east, even after peace comes in some way, it will be tough for Ukraine to settle into normalcy. Somehow, Putin's wrongheaded manifesto about there being no such people as Ukrainians, no Ukrainian language and no Ukrainian culture will have to be expunged entirely from the Russian consciousness and its political discourse. That will be no easy task. Anyone who knows Russia knows this will be a hard nut to crack. Of course, the war will end at some point, and Ukraine will find some way to return to a “normal” life. But note that I say “a” normal life... It will not be the one that existed before. It will be something different. It will be fraught with new dangers. It will be shaped by death, destruction, suspicion, and hatred for those who brought death and destruction to Ukraine. But the dream – and one must believe it is not merely a dream – is that Ukraine and its people will ultimately have the opportunity to deal with its national problems peacefully and politically. Surely that will happen. Just don't ask me when.